In yesterday’s post, I examined the HCSB’s translation of Matthew 6:9. Instead of “Hallowed be thy name,” the HCSB has “Your name be honored as holy.” In that post, I looked at the underlying Greek and discussed how the traditional rendering, while good in its day, is now a bit misleading to modern readers. I also discussed how our familiarity with the traditional rendering of well-known passages presents a challenge for translators. A few translations dare to improve the rendering of these favorite passages, but many just retain the traditional rendering because readers tend to balk when the wording of these passages is changed.

So which translations have been daring enough to change the traditional rendering of Matthew 6:9, and which have retained it? To find out, I’m going to use Accordance’s Search All feature, but before I do, I want to create a custom group containing all of my English Bibles.

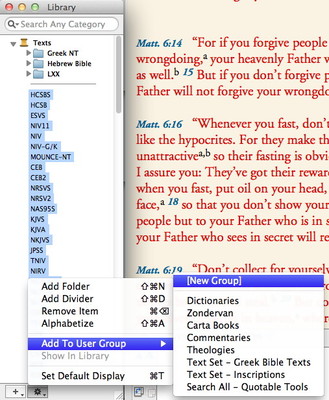

To create a custom group of modules, simply select the modules you want in the Library window, then choose [New Group] from the Add to User Group submenu of the Gear menu. A new folder containing all your selected modules will be added to the My Groups section of the Library window, and you can name it whatever you want. I named mine “English Bibles.”

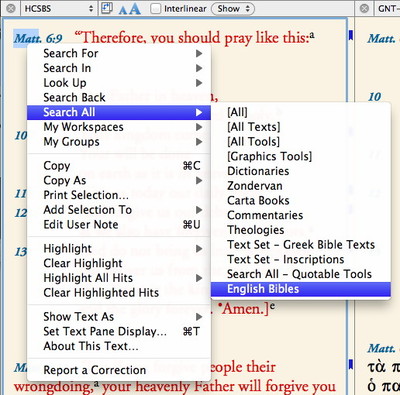

Now that I’ve created this group, I can search all the modules in that group at one time. In this case, I want to search these English Bibles not for a specific word, but for the verse Matthew 6:9. So I’ll simply right-click the verse reference for Matthew 6:9 in my main Bible tab and choose the English Bibles group from the Search All submenu of the contextual menu.

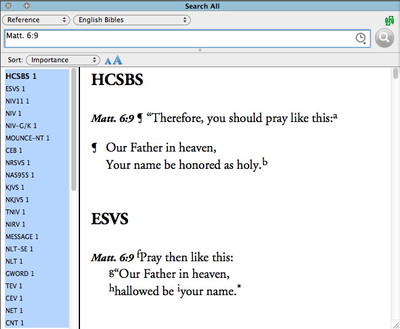

This will open a Search All window and find Matthew 6:9 in all my English Bibles. By selecting all those Bibles in the browser pane of the Search All window, I can see how each one renders that verse by scrolling through the results pane.

Of all the English Bibles I have in Accordance, a great many of them use “hallowed be your name,” departing from the King James translation only by replacing “thy” with “your.” Given the fact that the word “hallowed” has largely fallen out of use, this is somewhat surprising, and it shows how loath most translators are to change an expression which is often recited from memory. It is interesting to note that of the NIV family of translations, only the New International Reader’s Version (NIRV) makes a change here; the NIV, TNIV, and NIV11 all stick with “hallowed be your name.”

Most of the other renderings of this verse try to bring out the fact that the verb indicates a petition (rather than a merely descriptive statement) by using some helping verb like “let” or “may.” Many also try to make the idea of holiness explicit. These include “Your name be honored as holy” (HCSB), “uphold the holiness of your name” (CEB), “may your name be kept holy” (NLT second edition, WEB, CJB, BBE), “let your name be kept holy” (God’s Word), “May your holy name be honored” (TEV), “May your name be hallowed” (REB), and “May your name be held holy” (NJB). The idea of God’s holiness is probably also behind The Message’s much more paraphrastic rendering: “Reveal who you are.” A handful of other translations focus more on the idea of reverence and honor than on holiness per se: “may your name be revered” (Mounce), “may your name be honored” (NIRV, NLT first edition, NET), and “help us to honor your name” (CEV).

Right-clicking a verse reference to find it in all your English Bibles is a quick and easy way to make these kinds of comparisons, and doing so can help you better understand different aspects of the verse. Why does Jesus’ model prayer include the petition, “Let your name be holy”? If God is holy, then his name is holy, so there is no need to ask for it to become holy. However, not everyone regards it as holy, so the force of the petition is to ask that God’s name become universally honored as holy. This understanding accounts for why some translations focus on the concept of holiness while others focus on the need for honor. Skimming these translations reminds us to pay attention to both ideas in our own exegesis of the text.