Last night I demonstrated Accordance to a bunch of pastors at the Desiring God Pastor’s Conference. Since I don’t get too many opportunities to preach to pastors about sound exegetical method, I decided not to give a drink-from-the-firehouse-here’s-everything-Accordance-can-do demonstration. Instead, I showed how you can use the tools in Accordance to exegete a particular passage. After a brief overview of the interface, I opened 2 Samuel 11—the story of David and Bathsheba—and began unpacking the text using a variety of Accordance tools.

I won’t go into everything I did in that session, but my favorite part was showing how you can use Accordance’s analysis and highlighting tools to identify repeated words and key themes in a passage. This was my favorite part because there are so many interesting motifs to explore in 2 Samuel 11, and each of those motifs can form the backbone of an expositional sermon.

For example, I began by highlighting all the words in 2 Samuel 11 related to washing. Obviously, David sees Bathsheba “bathing,” and the text mentions that she was “purifying” herself from the ceremonial uncleanness resulting from her menstruation. Later in the passage, David tries to cover Bathsheba’s pregnancy by enticing her husband to return home and “wash his feet”—that is, enjoy all the comforts of home, including his wife’s companionship. Uriah, of course, refuses to return home. This motif of washing introduces a number of ironies. First, Bathsheba’s “purification” becomes the stimulus for a far more significant loss of purity. Second, the one person in this story who doesn’t “wash”—Uriah—is the only one who remains clean. As we say in the South, “That’ll preach!” A good expositional sermon, therefore, could work through the implications of this washing motif in 2 Samuel 11, communicating both the author’s literary artistry as well as a whole host of practical applications.

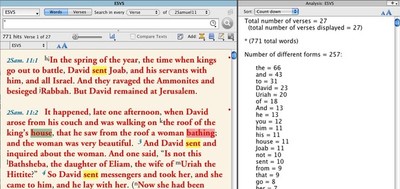

That, of course, is not the only literary motif in 2 Samuel 11. I went on to show how you could search for every word in 2 Samuel 11 (use the asterisk in word mode and define a range for 2 Samuel 11), then choose Analysis from the Details pop-up to get a list of all the words in the passage and the number of times they appear. Change the sort of the Analysis window from Alphabetical to Count Down and you’ll see immediately which words are used most often in that passage.

Doing this reveals a number of interesting things:

First, David and Uriah are the two people mentioned most often, while Bathsheba is mentioned only once. Clearly, the author is more interested in contrasting these two men than in focusing on the woman with whom David committed adultery.

Second, the word “house” is repeated ten times in this single chapter. Do a search for “house” in 2 Samuel 11 and you see the contrast between David, who expanded his own house by pillaging Uriah’s house, and Uriah, who remained faithful to build up the house of the king who had already betrayed him.

Finally, the word “sent” is also repeated numerous times in this passage. Examine that word, and you find that David, who is a man of action in almost every other passage, is constantly sending people to do his dirty work in 2 Samuel 11. The picture you get is of a man who is repeatedly manipulating things for his own benefit, rather than acting in service to the Lord or for the benefit of his people.

It should be easy to see how each of these motifs could form the outline of a good expositional sermon. For example, one could use the “house” motif in conjunction with Solomon’s statement in Psalm 127:1 that “Unless the LORD builds the house, those who build it labor in vain.” David resorts to ungodly means to build his own house, and it results in the judgment that “the sword shall never depart” from his house (2 Samuel 12:10). One could also point out that it was David’s second son with Bathsheba who makes the observation about the LORD building a house, so that you could end your sermon on a redemptive note.

If an expositional sermon derives its central message and structure from the text itself, exploring the text’s literary motifs and central themes provides a solid foundation upon which to build your sermon outline.