This morning I read the last chapter of 2 Peter, and I was struck by the fact that the author repeatedly addresses his readers as “Dear friends” (HCSB). Curious about which Greek word is being translated here, I opened a pane containing the ESVS (English Standard Version with Strong’s numbers) and could see right away that it is αγαπητος, “beloved.”

This got me wondering if the various authors of New Testament epistles addressed their readers differently. Since Greek has a special case for words of address—the vocative—I simply switched my search text to the Greek New Testament and searched for all vocatives.

Normally when searching for a grammatical characteristic like this, I would go to the Enter Grammatical Tag submenu of the Search menu, select a part of speech, and then constrain that part of speech by selecting tag details in the dialog box that opens. In this case, though, I’m interested in finding the vocative case no matter what the part of speech. I don’t want to have to specify vocative nouns, then vocative pronouns, then vocative adjectives, and so on; I just want to find all vocatives. To do that, I’ll choose the ANY Tag at the bottom of the Enter Grammatical Tag submenu of the Search menu. This inserts the ANY Tag into my search argument, and all I have to do is type the word “vocative.” (Abbreviations are also accepted, as long as you enter enough of the word to make it clear what you want.)

Notice, by the way, that I don’t have to remember some arcane set of codes in order to enter grammatical tags. I just enter the name of the tag or some reasonable abbreviation thereof.

Once I entered my search, I hit return to perform the search and got every vocative in the New Testament. I then clicked the Details button to get a bird’s-eye-view of what was found.

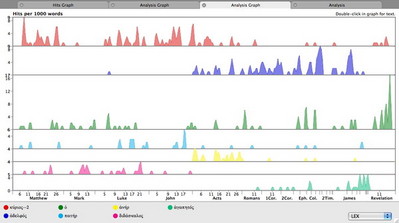

The Details Workspace lets you break down your search results in a variety of ways. I was specifically interested in the Analysis Graph, which plots multiple criteria across the entire search range. Here’s the Analysis Graph for all the vocatives in the New Testament, broken down by lexical form.

My search found more than seven lexical forms, but the Analysis Graph shows only the top seven, since anything more than that gets too confusing to be useful. The top two sections of the graph show the distribution of κυριος (“Lord”) and αδελφος (“brother”). Notice how “Lord” predominates in the gospels and Acts, while “brothers” is concentrated in Acts and the epistles. The same pattern holds true for other words as well. “Father” (light blue) and “teacher” (pink) occur frequently in the gospels, while “beloved” (light green) is used throughout the epistles. “Man” or “men” (yellow) as a form of address is used almost exclusively in the book of Acts, presumably because that book contains numerous sermons to the men of various cities.

The one section of this graph which is not particularly interesting is the third from the top (dark green), which plots the occurrence of the definite article. Since we searched for ANY vocative, we got all the vocative articles as well, and that’s now taking space on our graph that could be used by a more significant word.

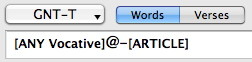

To exclude articles from my search, I can go back to the tab in which I performed this search and specify that I want ANY vocative which is not an article. Here’s how to do that:

The at symbol (@) basically joins two search criteria together to specify that both must apply to any word which is found. The minus sign indicates negation. So this search excludes all of the vocative articles.

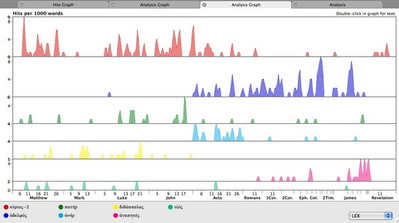

By clicking the Details button again, I see that the definite article has been excluded and υιος (“son”) has now become the seventh item on the graph. Interestingly, “son” as a form of address is, as we might expect, concentrated in the gospels. Yet notice that it only appears in the synoptic gospels and not in the gospel of John. Figuring out why that is might make for an interesting study in and of itself.

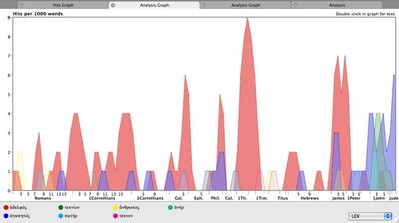

So far, we’ve seen a pretty clear distinction between the vocatives used in the narrative portions of the New Testament and those used in the epistles. But my original question had to do with the use of vocatives in the epistles. To narrow my focus to the epistles, I can go back to my search, open the more options section, and select a particular range to search. The pop-up menu that reads “[All Text]” lets you define ranges of books, chapters, and verses that you can then select whenever you like. If you don’t already have a range for the epistles, select Define Range from the bottom of the pop-up menu. In the dialog box which appears, enter “Epistles” for the Range name and “Romans-Jude” for the Range Definition. When you click OK to dismiss the dialog box, your new Epistles range will now appear in the pop-up menu. Simply hit return to update the search, then click the Details button to see the new Analysis Graph. Here I’ve customized the appearance of the Graph so that the various forms of address can all be seen together.

We see a number of interesting patterns here. First, Paul and James strongly favor αδελφος (“brothers,” in red) as their primary form of address, while the epistles of Peter, John, and Jude all favor αγαπητος (“beloved,” in blue) over “brothers.” John is also partial to τεκνιον (“little children,” in dark green).

Within the epistles attributed to Paul, we see other interesting patterns. As we might expect, the epistles to Timothy use the personal address τεκνον (“child,” in pink), along with one instance of ανθρωπος (“man,” in yellow). It is also interesting to see those places where Paul’s use of “brothers” as a form of address drops off. One such place is the first part of Romans, which is heavily theological and propositional. When Paul gets more personal and applicational in the latter part of the book, he addresses his readers as “brothers” far more frequently. Paul’s use of “brothers” as a form of address is also sparse throughout most of 2 Corinthians, and completely absent from Ephesians and Colossians. It would be interesting to examine why that might be.

Through some simple grammatical searches and the use of the Analysis Graph, it took me no more than a couple of minutes to explore how the various New Testament epistle writers address their readers. Doing so gives an interesting window into how each author interacted with his audience.