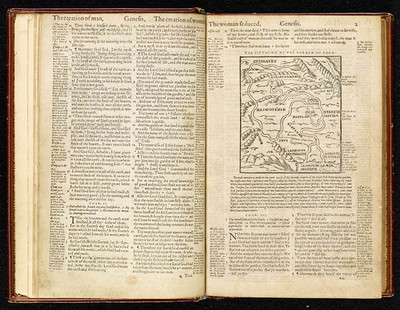

Let’s start with a little history. The first English study Bible was probably the Geneva Bible of 1560, a Protestant translation with notes written from a Reformed/Calvinistic perspective.

Now, marginal notes were hardly a groundbreaking innovation. Readers and copyists had been scribbling notes in the margins of hand-written manuscripts for centuries. But the Geneva Bible offered a relatively comprehensive set of notes on the entire Protestant canon, and those notes met the deeply felt needs of people at a pivotal moment in history.

Prior to the invention of the printing press, books were incredibly expensive to produce, so only the wealthiest of individuals—or entire communities—could afford to own them. Consequently, personal reading of the Bible was rare. Most people heard the Bible read in liturgical settings, where it was also immediately interpreted for them. With the advent of the printing press, individuals (or families) could suddenly afford to own a copy of the Bible and to read it for themselves. That, of course, meant that all sorts of people were now able to interpret the Bible for themselves.

Imagine yourself as a literate merchant able to bring home your first Bible. Churches are dividing and wars are being fought over differing interpretations of the Bible, and those differing interpretations are swirling around inside your head. You determine to read the Bible for yourself and try to sort out which interpretation is right. But you’re not a trained theologian, and even though you now have a translation you can read, much of what you’re reading still seems hard to understand. Where can you turn for help?

Now imagine yourself as a church leader trying to win the hearts and minds of the people in a community still wrestling with its own religious identity. Many of them don’t understand the sometimes subtle differences among the various churches, and their own personal reading of the Bible often only adds to their confusion. You want to guide them in their reading of the Bible, but you only have so much influence from the pulpit. What can you do to help them read the Bible “correctly”?

When the Geneva Bible was published, it offered an interpretive guide to individuals trying to read the Bible for themselves, and it offered Protestant leaders a powerful vehicle for disseminating their views. This first English study Bible therefore became very popular, so much so that even the crown-backed King James Bible took quite a while to supplant it.

The Geneva Bible’s sectarian marginal notes earned it both ardent admirers and passionate detractors. The King James’ lack of such notes eventually helped make it the universal choice among English-speaking Protestants, and few, if any, study Bibles were published over the next several centuries. It was not until the early twentieth century that the study Bible really came into its own. We’ll look at that stage in the history of the study Bible in my next post.