Although historically often at odds with each other, the Jewish and Christian faiths can potentially find common ground through related holidays occurring every Spring. I’m referring, of course, to Passover (Pesach) and Easter (Pascha). This year, Passover begins at sunset on April 19. Easter/Pascha falls on April 21 for most Catholic and Protestant churches and April 28 for most Eastern Orthodox churches. How do these holidays relate to each other, and what are the origins of these names? See below for a brief summary and follow the hyperlinks to much more detailed information.

Passover

The origins of the Jewish Passover can be found in Exodus 12. After centuries of slavery, God is about to lead His people out of Egypt, but not before delivering upon the threat given to Pharaoh of the tenth and final plague: the death of the firstborn. Preparations were to be made regarding Israelite families’ final meal in Egypt as well as a command to apply the blood of the animal eaten in that meal upon the doorposts and lintels of the houses. When the death angel visited Egypt that night, the firstborn was spared if the blood of a sheep or goat was found at the door of that home. Thus, it is said that the angel passed over each protected home, giving the name “Passover” to the event.

Later on, when Moses received the Law from God in the wilderness, the Israelites were commanded to commemorate the Passover event:

“In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, at twilight, there shall be a passover offering to the LORD, and on the fifteenth day of that month the LORD’S Feast of Unleavened Bread. You shall eat unleavened bread for seven days.”

(Leviticus 23:5-6, JPS Tanakh)

Although, technically two commemorations—Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread—the designation Passover today generally refers to the full celebration lasting eight days. Unleavened bread is eaten as part of this commemoration because the Israelites had to eat the Passover meal in a hurry and did not have time to wait for yeast to make bread rise before it could be baked. The JPS Dictionary of Jewish Words describes the traditional Passover observance in its entry, “Pesach”—

Pharaoh allowed the Israelites, led by Moses, to flee. They left Egypt in such haste that they did not even have time for their bread to rise. They had to eat unleavened bread, or matzah. This is the basis for one of the most important traditions of Pesach: eating only matzah, not bread or leavened products. During the week of Pesach, special cookies and cakes made with matzah meal and other pesachdik ingredients are eaten.

Before Pesach begins, a Jewish family cleans the entire home—especially the kitchen—to remove all crumbs and traces of regular bread and bakery products, called hametz. Many families even change their dishes and silverware, using special sets reserved for Pesach.

Pesach begins with a long, carefully ordered meal and service called a seder. On the table is a seder plate with symbolic foods: beitzah, maror, haroset, zeroa, and karpas, whose meanings are explained in the course of the seder. Other special items, such as matzah, Elijah’s Cup, and sometimes Miriam’s Cup, are also on the table. Participants use a prayer book called a haggadah, which includes the story of the holiday, the Four Questions, and traditional songs.

While Pesach is observed primarily at home, there are synagogue festival services on the first and last days. Biblical readings are from The Song of Songs, one of the five megillot. A Yizkor service is held on one of the last days.

Passover Seder Plate from Pictorial Library of Bible Lands: Cultural Images of the Holy Land

Joseph Tabory, in The JPS Commentary on the Haggadah (the most extensive source I know on the subject!), writes that the seder meal mentioned above “is the founding ceremony of the Jewish people, a ceremony based on the centrality of the family as the basic Jewish institution.” Tabory further states that the seder observance “is…a celebration of freedom of person and of nation.”

Pesach to Pascha

Sometimes you might see mention of Passover, especially when celebrated in non-English traditions, referred to its Hebrew name: פֶּסַח or the English transliteration, pesach. This word occurs about 74 times in the Hebrew Bible. When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek (known as the Septuagint, or abbreviated as LXX) beginning around 200 BCE, the Greek word πάσχα/pascha (or variants φασεκ, φασεχ in 2 Chronicles). When the New Testament writings were composed in the first century, the precedent set in the LXX was followed, and pascha was used to refer to the Passover around 29 times.

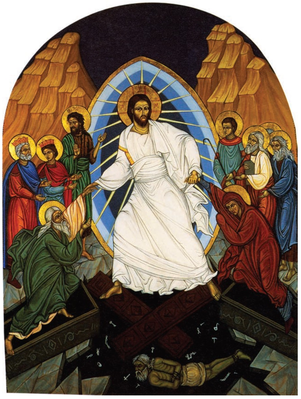

Image to the right: Resurrection of Christ icon from The Orthodox Study Bible

In the New Testament, the crucifixion of Jesus Christ is directly connected to the Jewish Passover celebration by way of both timing and theology. Jesus is specifically arrested and crucified before the Passover for fear of riots once an influx of pilgrims appear in Jerusalem (see Matt 26:2 and Mark 14:2). Jesus’ “Last Supper” is a Passover meal that he celebrated with his disciples (see Matt 26:17). The crucifixion takes place on the Jewish Day of Preparation for the Passover (see John 19:14, 31) “when the Passover lambs [were] slaughtered in the Temple” (see note in the Jewish Annotated New Testament). The Jewish Babylonian Talmud also gives witness to Jesus’ crucifixion taking place on the eve of Passover (see Sanhedrin 43:1, II.1.C). The timing of these events was not lost on the early Christians who saw Jesus Christ as the “Passover lamb” (see, for instance, 1 Cor 5:7). In Christian celebrations, it is not the day of the crucifixion (“Good Friday”) that receives most attention, but rather the “Resurrection Sunday,” which is primarily referred to as Pascha or Easter, although the terms are sometimes used generically to also include the events leading up to the day.

Easter

Interestingly, although using a variety of words to refer to the Passover in both Old and New Testaments, the Latin Vulgate retains pascha for many references to the Passover, especially in the New Testament. In fact, worldwide, most Christians refer to their holiday as “Pascha,” and not “Easter.” Primarily, it is only English-speaking Catholics and Protestants who use the word Easter. Why is this?

Not a lot is known for certain about the English word Easter. In fact, everything we know about the word comes from one mention in passing by the Venerable Bede (673-735). According to him, the word referred to an Anglo-Saxon goddess, Ēostre. In his day, the pagan springtime festival honoring the goddess had already been replaced by Christian Pascha celebrations, but the old name for the occasion had still stuck around (see articles in The Encyclopedia of Christianity and The New Unger’s Bible Dictionary for more information). Although some have wanted to connect Ēostre to the Canaanite goddess Asherah, mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, there has not been a definitive connection made to date, to my knowledge. The explanation from Bede is the only real information how “Easter” came to be known for Pascha in English-speaking Christian traditions. English-speaking Orthodox Christians still generally refer to the holiday as Pascha as do most non-English-speaking Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant Christians.

Final thoughts

We occasionally receive correspondence objecting to the use of “Easter” in one of our newsletters or other marketing material since the name, as described above, has pagan roots. Personally, I don’t get too hung up on this kind of thing. I believe God honors our intentions with such designations, but if we want to remove all pagan references from the calendar, we have lots of work to do (Thor’s Day anyone?). My faith tradition primarily uses the name Pascha instead of Easter, and I believe that to be a good, biblical substitute if anyone is especially concerned about such things.

Regardless of whether one goes by the label of Jewish or Christian, the festivities of Passover/Pesach/Pascha/Easter offer us a time of celebrating redemption and renewal. We thank God for his active role in seeking us out and providing means for our salvation. We reflect upon the new opportunities given to us to serve him out of thankful hearts. Even with the differences that sometimes divide us, we can surely agree on these common ideas of God’s redemptive acts on our behalf.

This year Passover and Good Friday (in the West) observances fall on the same day (April 19). What determines the dates for Passover/Pesach and Pascha/Easter? The answer to that question can be complicated, but it can be found with the right tools in the Accordance Library. Stay tuned for an upcoming post to address that issue!