In my last post, I argued that the practical value of learning Greek and Hebrew becomes readily apparent when dealing with situations where careful exegesis of the biblical text is absolutely necessary, such as “[arriving] at a clear position on the latest theological controversy.” Not long after writing that post, I stumbled across a timely example.

In my last post, I argued that the practical value of learning Greek and Hebrew becomes readily apparent when dealing with situations where careful exegesis of the biblical text is absolutely necessary, such as “[arriving] at a clear position on the latest theological controversy.” Not long after writing that post, I stumbled across a timely example.

In an interview with Christianity Today, the founder of a conference on issues of sexuality made the following claim:

One way would be to say that eros is not intrinsically sexual. It’s never how that word is used in ancient Greek. The Greeks had a different word, venus, that was used to describe explicitly sexual love.

My purpose here is not to critique this person’s overall position, which needs to be evaluated by looking at all the arguments he uses rather than just this single point. I simply want to look at this particular statement about Greek words and their meaning. If the Greek language makes a distinction between what we might call “romantic love” (eros) and “explicitly sexual love” (venus), then we should be wary of reducing the concept of eros to a strictly sexual attraction. This is the kind of distinction preachers can build whole sermons around!

The problem is that venus is not actually a Greek word at all! This is something that should be readily apparent to anyone who has managed to learn the Greek alphabet, since Greek has no letter “v”. Perhaps I’m especially sensitive to this, since I learned early on that my name David is variously spelled with a ‘b’ (Δαβιδ) or a ‘u’ (Δαυιδ) in Greek.

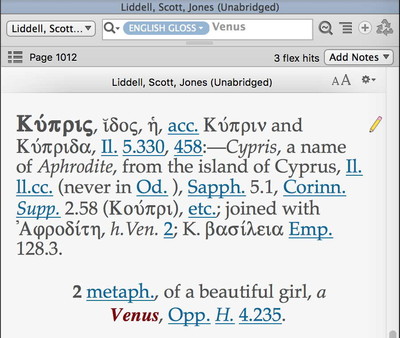

Just to be fair, I searched the classical Greek lexicon by Liddell, Scott, and Jones for any Greek words that might approximate “venus”, such as υενος, υηνος, βενος, and βηνος. The only one I found was υηνος, which means “swinish.” I also searched the English Gloss field of this lexicon for “Venus.” This turned up several terms related to Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and desire.

Of course, we should already have noticed that the word “venus” is the name of a pagan goddess. In fact, Venus was simply the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite. We may be less likely to remember that eros, which actually is a Greek word for “love,” is also the name of a Greek god, who is more popularly known by his Roman equivalent: Cupid.

The argument quoted above tries to distinguish between two Greek words, but one of them is actually a Latin word, and so the argument falls apart completely.

How could the author have made such a mistake? Because he probably derived this argument not from a careful study of Greek, but from a loose recollection of a passage from C. S. Lewis’s book, The Four Loves:

The carnal or animally sexual element within Eros, I intend (following an old usage) to call Venus. And I mean by Venus what is sexual not in some cryptic or rarified sense—such as a depth-psychologist might explore—but in a perfectly obvious sense…

Note how Lewis decides to use Venus as a term for identifying the “animally sexual element within Eros” (as opposed to higher elements of romantic love). He says that this convention follows an “old usage,” but he makes no claim that it is an ancient Greek usage. Lewis would have known all too well that he was mixing the names of a Greek god (Eros) and a related Roman goddess (Venus), but he didn’t care, because these terms were a convenient short-hand for the concepts he wanted to discuss. I think the individual I quoted above merely read this passage from Lewis and mistakenly concluded that the distinction Lewis was making was actually rooted in the Greek language itself. He then repeated a completely false “fact” about Greek.

The more you study Greek and Hebrew, the more you can see the problems with these kinds of arguments. The author may have a point worth listening to, but this particular appeal to the authority of the Greek language should be summarily dismissed.