In those formative years, my biblical profs held sway over me, and I developed a distrust for theology in comparison with biblical studies. I admit that I am sometimes still skeptical of systematic theology in particular, but I have grown to appreciate theology in general, especially when presented from a historical perspective.

This division in the disciplines was part of the prompting for the Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible, which we are releasing today for the Accordance Bible Software Library. This recent series, still in process, seeks to recapture the role of dogma in understanding the Bible. In the series preface the writers draw upon the writings of the Early Church in their defense: “Irenaeus assumes that there is a body of apostolic doctrine sustained by a tradition of teaching in the church. This doctrine provides the clarifying principles that guide exegetical judgment toward a coherent overall reading of Scripture as a unified witness.” Further, writes series editor, R. R. Reno, “This series of biblical commentaries was born out of the conviction that dogma clarifies rather than obscures.”

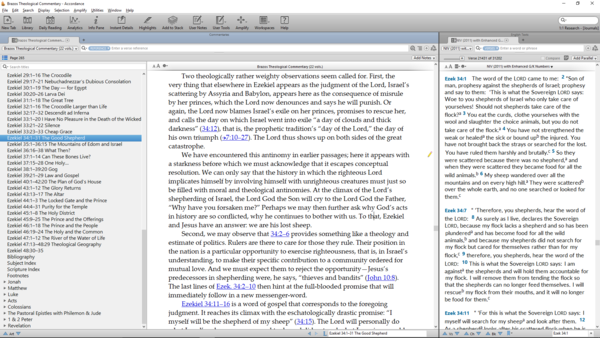

Click/tap the image above for a larger view of Robert W. Jensen’s Ezekiel volume of the Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. NIV text available separately.

Unlike many commentary series, the Brazos Theological Commentary is written by theologians rather than biblical scholars in the traditional sense. The guiding theological framework for the perspective of the series is the Nicene Creed, which is arguably the most important doctrinal statement in the history of the church. Individual writers are not held to any particular translation to use as the base for the commentary, and they are not even restricted to format. Some commentators may write verse by verse, while others focus more on a passage at a time. The outlook of the series is purposefully ecumenical in scope. Thus, the Brazos series results in a very eclectic, but extremely readable exposition of the Scriptures.

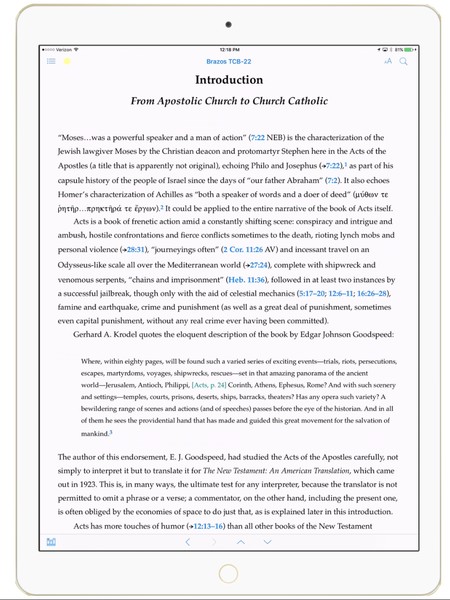

Click/tap the image above for a larger view of Jaroslav Pelikan’s introduction to Acts in the Brazos Theological Commentary.

Consider this excerpt on Matthew 4 from well-known theologian Stanley Hauerwas. Note his use of biblical content, theology, and historical insight—all intertwined into a cohesive explorationof the temptation of Jesus:

The devil, therefore, thinking that Jesus’s fast might have weakened him, approaches Jesus just as he had approached Eve. Eating may be the devil’s first line of attack because eating gets to the heart of our dependency—a dependency we try to deny. He initiates a conversation with Jesus, as he had Eve, with what seems to be an innocent remark, but a remark designed to create doubt: “Did God say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden?’” (Gen. 3:1). “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread” (Matt. 4:3). The trick, of course, that Eve did not recognize is to try to answer the devil on the devil’s own terms. Bonhoeffer observes that Eve’s disobedience began as soon as she assumed that she could answer the serpent’s question on God’s behalf, for the question was designed to suggest that she and Adam could go behind the word of God and establish for themselves what the word entailed. In short, the devil’s question invited them to assume that they were equal with God. Bonhoeffer notes, therefore, that the serpent is a representative of religion because his question is “religious,” assuming that the questioner knows more about God than can be known by a creature (1962, 66–69).

The devil exists as rage, but his rage does not cloud his cleverness. He is crafty. He therefore suggests to Jesus that, if he is the savior of Israel, he should then do what God had done for Israel in the wilderness, that is, provide food. Jesus, who will feed thousands with a few loaves of bread and a small number of fish, could turn the stones into bread. But Jesus refuses, quoting Deut. 8:3, which tells the story of how God had humbled Israel by letting her go hungry before sending manna. God says, I fed “you with manna, with which neither you nor your ancestors were acquainted, in order to make you understand that one does not live by bread alone, but by the very word that comes from the mouth of the LORD.” God is indeed in the business of providing food, but Jesus rejects Satan’s proposal because Satan would have us believe that food and the word of God can be separated.

Christians believe that Jesus is the word that we now eat in his very body and blood in the Eucharist. But that gift, like the gift of manna to Israel, makes us vulnerable to the same temptations that the devil used to encourage Israel to abandon God’s law, to tempt Jesus, and to make the church unfaithful. The very people whom God has gifted with his body to be his witness for all people are constantly tempted to betray that which has been given them. We become, like the Pharisees, scribes, and Sadducees, leaders who assume that our task is to protect “the people” from the demands of the gospel. We simply do not believe that God’s word, God’s love, can sustain us.

Slowly over the years, I’ve been able to conclude that biblical studies should not and cannot be divorced from theology. The Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible should not be seen as a replacement to more traditional biblical commentaries, but I would recommend this series as a necessary addition to them.

Brazos Theological Commentary (22 Volumes)

Regular Price $715