Article Author: David Lang

I used to think I was something of a history buff, but working on the Accordance Timeline Expanded Edition has taught me that I still have a lot to learn. Here are five things developing the new Timeline taught me about history.

1. It Has Always Been a Small World After All

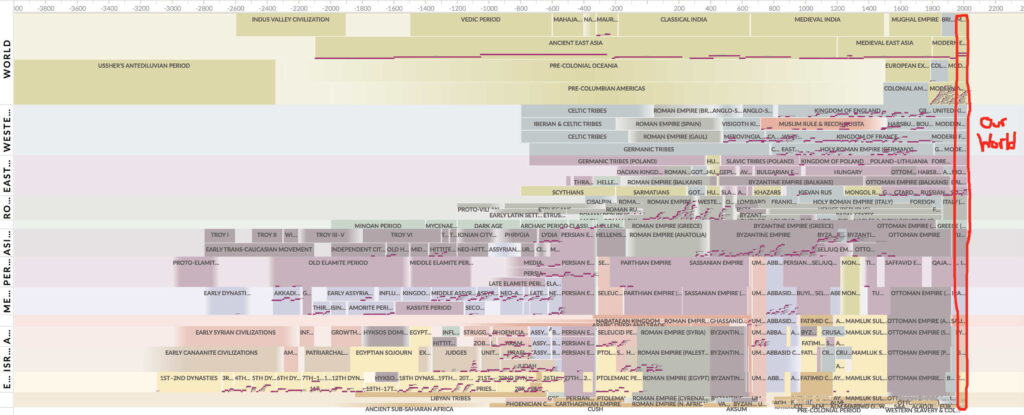

If 2020 has taught us anything, it is how very small our world really is: in mere months, a virus originating on one side of the planet has wreaked havoc across the globe. We tend to think that kind of worldwide interconnectedness began with the advent of modern air travel, but the airplane has only sped up connections which have existed from time immemorial.

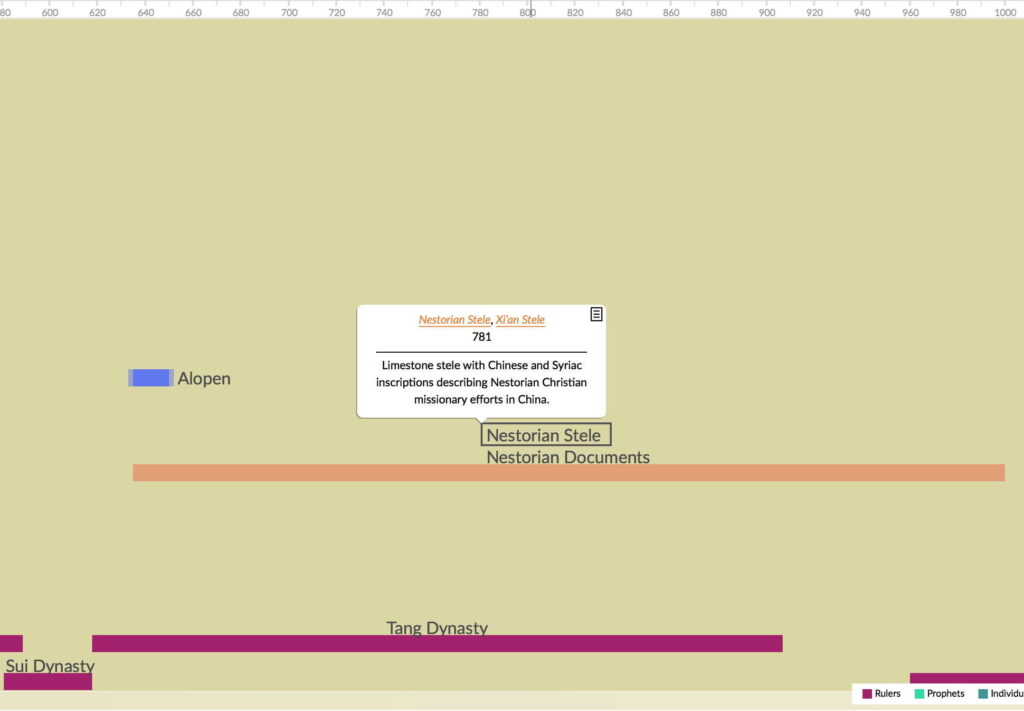

East and West have never been as bifurcated as our history classes and textbooks make it seem. Most of the Germanic tribes which destabilized the Western Roman empire had been pushed west by a series of invaders from the east (Huns, Avars, Khazars, etc.). Nestorian Christians were engaging in missions to China more than a thousand years before Hudson Taylor.

Silk road and Black Sea trade brought Asian technological innovation and luxury goods—along with pandemics like the Black Death—to Medieval Europe. Landmark events in Western civilization, such as the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, and the exploration of the New World can all be directly traced back to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks.

There is a sense in which all history is world history.

2. We Are Part of a Much Larger Story than We Realize

Zoom out on the Expanded Timeline far enough to see the entire period of recorded history (3000 BCE/BC–2020 CE/AD), and you’ll be struck by how comparatively brief “modern” history is.

Of the modern nation states we know today, it is surprising how many were established or took their current form in the last 100 years or so. Among post-monarchical republics, the United States is among the most venerable at only 244 years old. These are mere blips when compared with empires and civilizations which lasted for hundreds or even thousands of years. When we consider how short-lived our modern civilizations really are, the chronological snobbery to which we moderns are so prone suddenly seems incredibly foolish.

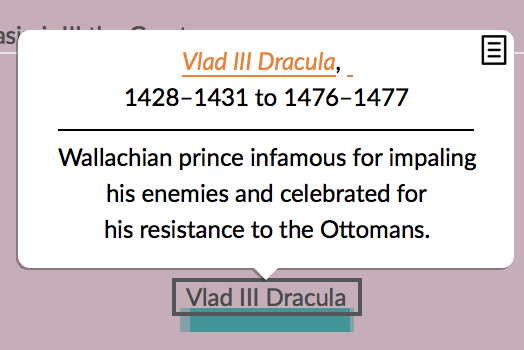

3. Utopia Means “No Place”

When Thomas More (who is on the Expanded Timeline) wrote about an ideal society, he named it “utopia”, from the Greek meaning “no place.” Those who want to look back to some period of history as an ideal time are sure to find that their utopia had its dark underbelly. All those historical figures we may want to regard as “good guys” inevitably turn out, upon further investigation, to be deeply flawed. On the other hand, it is often surprising how often the “bad guys” end up making contributions most of us would regard as positive. Historical figures don’t always—or even often—divide neatly into heroes and villains, no matter how much we may want them to.

4. Church History Has Always Been Messy.

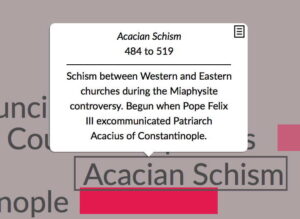

You’ll sometimes hear it said that the Christian church was essentially united until the Great Schism of 1054 CE/AD or the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, but the story of church history has always been messier and more complicated than that. Even as Christians struggled to survive in the face of Roman persecution or Persian and later Islamic conquests, Christians were consumed with internecine conflicts over doctrinal issues, questions of ecclesiastical authority, and personal rivalries between church leaders—not unlike today.

Dig into the Christological controversies of the fourth and fifth centuries and you’ll discover schisms you never heard of before. You’ll see that groups pronounced heretical typically continued to maintain their orthodoxy and fight for acceptance long after the issue was “settled” by an ecumenical council. You’ll also see that groups which felt under-represented at those councils often disputed their “ecumenical” status. Once Christianity became the official religion of various empires and states, political conflicts often spilled over into the church. Conversely, ecclesiastical disputes often led to popular riots and political coups.

By the way, this is not unique to Christian history. Islamic history is likewise complicated, with civil wars between rival caliphates, conflicts among rival sects, and sometimes shifting alliances with non-Muslim groups. Jewish history likewise has its rival sects and internal disputes, even during the diaspora when Jews struggled to determine whether they had a better chance of survival with Muslim or Christian rulers.

It is not unusual to hear people complain that “We have never been more divided than we are today.” Explore the Expanded Timeline, and you’ll likely be relieved that we haven’t yet descended into civil war or started maiming and crucifying one another!

5. The Arguments are Never Really About What They Seem to be About.

When you get married, you learn pretty quickly that marital conflicts are usually about deeper issues than the actual point of conflict, which can be laughably trivial. The same is true of the religious conflicts which lead to schisms, the founding of new churches, and sometimes bitter violence. When we look at the actual point of conflict from the outside, it may seem strange to us: does Christ have one or two natures? What about one or two “energies” or “wills”? Are icons a legitimate element of Christian worship or are they idolatrous? Is Christ physically present in the Lord’s Supper or is it merely symbolic? At various points in history, Christians argued these points and clung to their positions with a vehemence that the most ardent sectarian of today would find extreme. That passion was usually driven by a concern for deeper issues than the actual subject of debate. They believed they were defending the goodness of God, or Christ’s divinity, or his humanity, or the centrality of the gospel, or the authority of Scripture, or centuries of Christian tradition. They also feared that those on the opposite side of the debate were compromising or betraying those central aspects of their faith.

Understanding this dynamic ought to help us grasp the passion with which today’s combatants argue their sides of today’s debates. The actual point of disagreement may seem trivial, but we should look for the deeper issues each side believes to be at stake.

For me, the great value of studying history is the clearer perspective it gives me on the world in which we now live.

It helps me realize how interconnected our world really is, and makes me less provincial in my thinking.

It helps me listen more attentively to those whose perspectives seem nonsensical to me and whose vehemence strikes me as excessive.

It helps me realize that though our world sometimes seems to have gone mad, it has always been a “mad, mad, mad, mad world.” In fact, there were many periods in history which make today’s madness seem mild by comparison.

Finally, studying history helps shatter my naïve assumptions about history’s “good guys” and “bad guys” and my illusory dreams of the “good ole’ days.” To quote Billy Joel, whose history of the Cold War era appears as an Easter egg on the Expanded Timeline: “the good ole’ days weren’t always good, and tomorrow ain’t as bad as it seems.”

That’s an important reminder to us all.